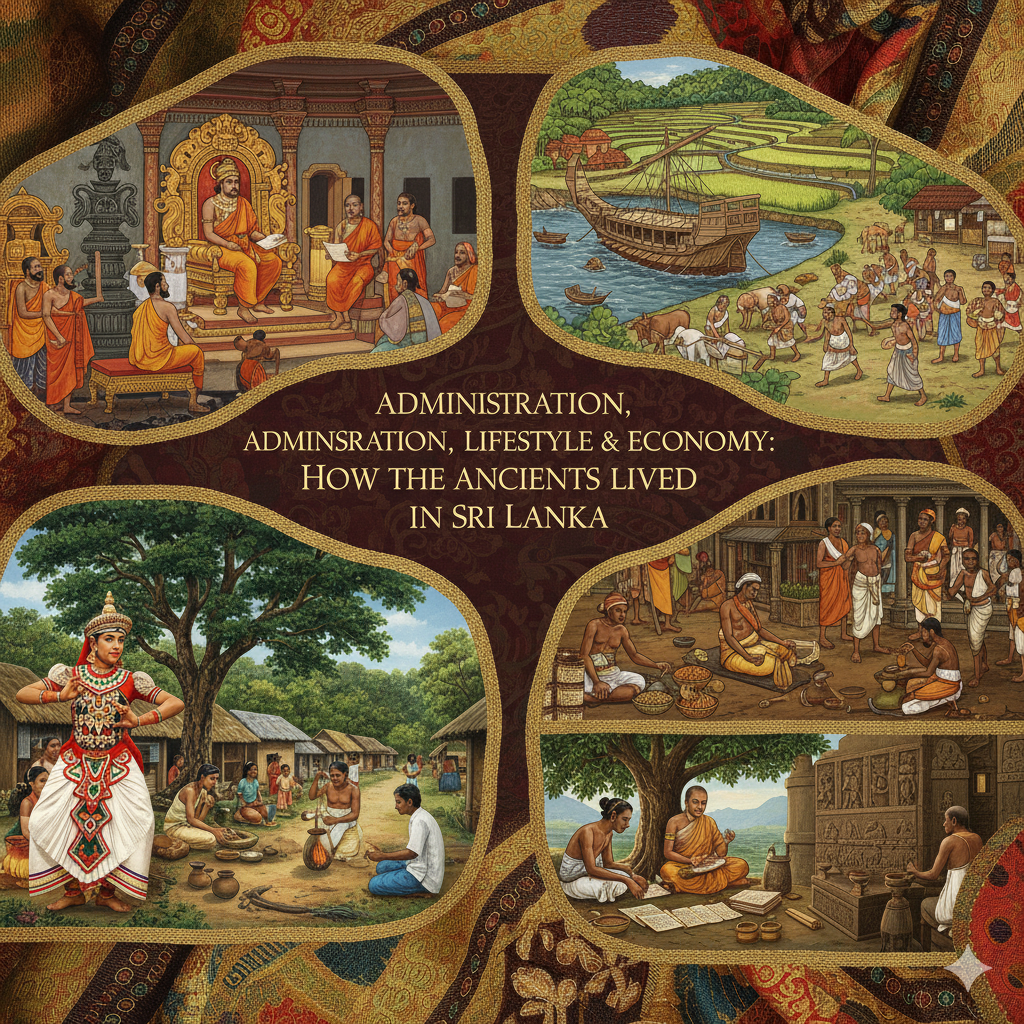

Administration, Lifestyle & Economy: How the Ancients Lived in Sri Lanka

- November 14, 2025

- eunoialankatours

- 4:01 pm

An island of chieftains and the rise of monarchy

Long before Sri Lanka’s grand irrigation tanks and dagobas, the island was a mosaic of small chiefdoms. Early Indo-Aryan settlers migrated from the Indian subcontinent around the 5th century BCE and founded riverbank villages along the Malvatu Oya and other rivers. These settlers mixed with earlier island inhabitants and created an early Sinhalese culture, while Tamil groups arrived later from southern India. According to the island’s chronicles, these settlements were headed by gamanis or rajas, local chieftains who controlled small territories and ruled from rustic forts. Over twenty such chieftains governed Anuradhapura and the surrounding districts during the third century BCE, each presiding over his own clan and fields. In this world of competing leaders, allegiance depended on kinship and the ability to provide food and security.

As agriculture flourished and wealth accumulated, power began to centralise. Around the 2nd century BCE King Dutugemunu (Duttagāmanī) unified the island under a single monarch after defeating numerous chieftains. Succession became hereditary: if the king had a brother, he inherited the throne; otherwise the crown passed to his eldest son or, failing that, to his nephew. Three categories of royal officials supported the king. Palace officers such as the Porohitha (chief priest) performed religious rites and counselled the king, while gate-keepers (doratu-pala) controlled palace access and maintained security. A central administration headed by the senpathi (commander-in-chief) and other military officers oversaw the army and treasury. Scribes recorded grants and maintained state records; they were called mahale or mahalekhaka in the early Anuradhapura period and later became known as mahalearaksamanan. A board of ministers (amathi) advised the king; these councils, later called amatigana or amatya mandala, provided continuity and managed provincial governors. Most officials were relatives of the ruler, so power remained concentrated around the royal family.

The island was divided into three main provinces: Rajarata (Pihiti Rata) in the north and north-central region, Ruhuna (Rohana Deshaya) in the south and southeast, and Maya Rata (Malaya Desa) in the hill country. These provinces were governed by Apa or Mapa, relatives or trusted nobles of the king. Each province was subdivided into rata, administrative districts overseen by officials known as Ratiya or Ratikā. The smallest unit was the village (gama); an elected or hereditary headman (gamika or, later, gamladda) settled disputes and organised communal labour. Judicial duties were usually performed by village elders or provincial governors, while the king served as the final arbiter in serious cases. Buddhism, introduced by emissaries of Emperor Aśoka around 247 BCE, deeply influenced governance; monks counselled the king and legal principles drew on Buddhist ethics.

Village life: houses, food and festivals

For ordinary islanders, life revolved around the village. Settlements were deliberately clustered below irrigation reservoirs so that water could be channelled easily to nearby paddy fields and household gardens. A typical village contained dwellings of wattle and daub, paddy fields, a reservoir or perennial stream, grazing land for cattle and buffalo, and a patch of forest for fuel and fruit. Houses stood on higher ground to escape floods, while footpaths wound through coconut palms and home gardens. Villagers developed a strong culture of mutual help; community members assisted each other with ploughing, irrigation repairs and harvesting, a practice later known as rajakariya (king’s duty).

Food and daily routines

Rice was the staple crop and the basis of most meals. Two main harvests, Yala and Maha, were produced annually using an elaborate network of irrigation tanks. When rains failed, finger millet and other drought-tolerant grains were grown. Villagers ate rice with curries made from vegetables, pulses and sometimes fish or meat. Buddhist beliefs discouraged killing animals, so animal husbandry was limited mainly to rearing cattle and buffalo for ploughing and milk. Dairy products—milk, curd, buttermilk, ghee and butter—were prized.

Cooked rice dishes such as kiribath (milk rice) and hoppers were served at festivals. Coconut milk and chili peppers flavoured almost every dish. Spices—including cinnamon, native to Sri Lanka—were abundant. Palm sap fermented into toddy or distilled into arrack provided a mild alcoholic drink. Tea, introduced much later, became a symbol of hospitality: guests were offered a cup whenever they arrived.

Homes, clothing and crafts

Men and women typically wore cotton garments; cotton was grown locally to supply cloth. Simple jewellery of beads and metals adorned ears and necks. Metalworking was highly developed; blacksmiths forged iron ploughs and weapons, while copper was used for roofing the Lovamahapaya monastery. Villages were largely self-sufficient; potters, basket-weavers, drummers and washerwomen belonged to hereditary guilds and lived in clusters near the village. Women enjoyed considerable freedom and independence—inscriptions show women donating caves and property, and chronicles describe kings seeking their mothers’ counsel.

Daily life was punctuated by religious festivals and rituals. The Sinhalese and Tamil New Year in April marked the sun’s transition from Pisces to Aries; astrologers determined the exact times for rituals, and villagers refrained from work during auspicious periods. Full-moon days (poya) were Buddhist holidays when temple visits and offerings replaced farm work. These festivals reinforced communal bonds and mirrored the rhythm of the agricultural calendar.

An agrarian economy intertwined with trade

Agriculture and irrigation

The economy of the Anuradhapura kingdom was overwhelmingly agricultural. Vast reservoir and canal systems—many constructed under kings such as Pandukabhaya, Vasabha and Mahasena—channeled monsoon rains into storage tanks that irrigated paddy fields throughout the dry season. These works enabled the island to be largely self-sufficient in rice and supported a population that may have reached hundreds of thousands. Cotton, sugarcane and sesame were also widely cultivated, and finger millet served as a drought-tolerant substitute for rice. Surpluses of rice and other produce were exported when yields were abundant.

Trade networks

Although most villages produced what they consumed, the capital Anuradhapura became an important commercial hub. Traders from as far as Greece, Persia and Arabia lived there; Greek settlers (called Yavanas) were settled at the city’s western gate as early as the 4th century BCE. The island’s strategic location in the Indian Ocean and its natural harbours—Mahatittha (Mannar) and Gokanna (Trincomalee)—made it a transit point for international trade. Foreign merchants acted as middlemen, exporting Sri Lankan goods and importing luxuries.

Exports included gemstones, spices, pearls and elephants, which were prized in Indian and Roman markets. Imports comprised ceramic ware, silks, perfumes and wine, showing that island elites enjoyed foreign luxuries. By the ninth century Muslim traders had established coastal communities, and Arab settlements later evolved into Sri Lanka’s present-day Moor community. Stone inscriptions refer to markets (bazaars) in Anuradhapura, and coins were used to pay fines, taxes and for everyday transactions. The earliest coins (2nd century BCE) were silver kahavanu, imprinted with elephants, horses, swastikas and the Dharmacakra. Uncoined gold and silver were also accepted for trade.

Taxes and royal revenue

To finance irrigation works, the army and the court, kings levied a grain tax (bojakapati) on cultivated land and a water tax (dakapati) on the use of reservoirs. Customs duties were imposed at ports on imported goods. Those unable to pay taxes in cash or kind performed public labour—repairing tanks, maintaining canals or working on royal projects. The king’s treasurer, or Badagarika, administered these levies, ensuring that state revenue flowed to the palace and temples.

Conclusion

The early civilisations of Sri Lanka were neither primitive nor static. From scattered villages ruled by chieftains they evolved into a centralised monarchy with complex administrative structures. In this world, water was life: irrigation networks sustained agriculture, defined village layout and underpinned both economy and spirituality. Rice cultivation, Buddhist ethics and community cooperation shaped daily routines, while trade brought foreign ideas and luxuries to royal courts. The legacies of this period—an enduring village culture, awe-inspiring reservoirs and a spirit of hospitality—continue to inform Sri Lanka’s identity today.