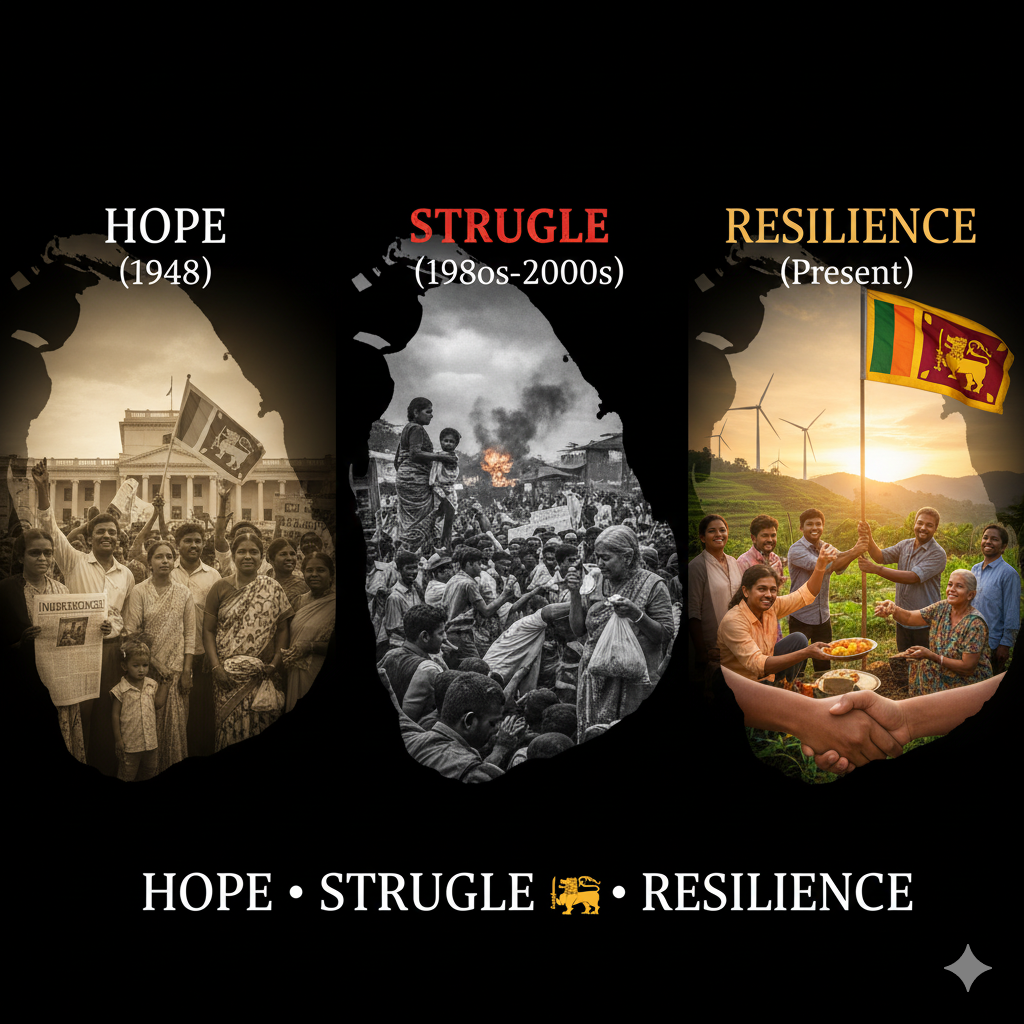

Sri Lanka After Independence: A Human Story of Hope, Struggle andResilience

- November 14, 2025

- eunoialankatours

- 9:28 pm

When Don Stephen (D.S.) Senanayake raised the newly designed Lion flag on 4 February 1948, people thronged the streets of Colombo. After centuries of colonial domination, the island then known as Ceylon finally became an independent state within the British Commonwealth. The United States recognised this status on the same date, noting that Ceylon became an independent dominion under an agreement between London and the Ceylonese government. Senanayake, a quiet but determined Buddhist farmer who had worked for years on agricultural reforms, became the country’s first prime minister. In those early days, hope was palpable; families imagined futures outside of plantation labour, and school children learned the national anthem in Sinhala and Tamil.

That hope, however, co-existed with enduring colonial structures. Under the Soulbury Constitution—drafted by Senanayake and British scholar Sir Ivor Jennings—the new House of Representatives held authority over domestic affairs, yet defence and external affairs remained in the hands of a British governor-general. Even after independence the island remained a Commonwealth realm, and it was not until 16 May 1972 that a Constituent Assembly proclaimed an independent republic. This complex transition shaped the early decades of freedom: ministers worked to build irrigation schemes, but the British crown’s representative still signed laws; Sinhala, Tamil and English newspapers celebrated independence while warning of imported goods shortages.

The Seeds of Division

In 1956 the charismatic politician S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike rode a wave of Sinhalese nationalism into power. He terminated a defence agreement with Britain and sought to “restore national culture”. One of his defining acts was the Official Language Act No.33 of 1956—better known as the Sinhala Only Act. This law replaced English with Sinhala as the sole official language, marginalising Tamil speakers and symbolising the majority’s desire to assert a Sinhala-Buddhist state. Tamil politicians and civil servants suddenly found themselves unable to work in their own country’s bureaucracy; students were forced to sit for exams in a language they had never learned. The Act galvanised Tamil youth into politics, laying the seeds for separatist movements that would erupt decades later.

New Constitutions and Centralised Power

The First Republican Constitution (1972)

By the early 1970s, dissatisfaction with colonial-era frameworks and rising socialist ideals led the United Front government of Sirimavo Bandaranaike to draft a republican constitution. Adopted on 22 May 1972, the constitution changed the country’s name from Ceylon to Sri Lanka. It declared the island a unitary state, recognised Sinhala as the sole official language, and gave Buddhism a priority position. Parliament’s term was set at six years, and a non-executive president replaced the governor-general. For many Sinhalese the reforms represented a long-awaited assertion of sovereignty; for Tamils they signified constitutional confirmation of exclusion.

The Second Republican Constitution (1978)

The 1977 general election delivered a landslide victory to the United National Party (UNP) under J.R. Jayewardene. Seizing this mandate, Jayewardene introduced a new constitution on 7 September 1978. It replaced the Westminster-style parliamentary system with a unicameral parliament and an executive presidency, making Jayewardene Sri Lanka’s first executive president. The reforms introduced proportional representation but simultaneously allowed the president to dissolve parliament after one year. Power that once resided collectively in the legislature shifted markedly to one individual. Over time, many Sri Lankans came to associate the executive presidency with concentrated authority and weakened democratic checks—observations echoed decades later in public debates about constitutional reforms.

Key Amendments and Attempts at Balance

The new constitution has been amended numerous times. The 13th Amendment (certified on 14 November 1987) made Tamil an official language, named English a link language, and established Provincial Councils, devolving power away from the centre. It was a response to growing Tamil grievances and part of an Indian-brokered peace accord. The 19th Amendment (April 2015) sought to reverse prior excesses by re-establishing independent commissions (for elections, police, public services and human rights) and limiting the president’s powers. However, the 20th Amendment passed in October 2020 effectively repealed many of those reforms; according to independent reports, it allowed the president to hold ministries, appoint and dismiss ministers, dissolve parliament after two-and-a-half years and abolished the independent Constitutional Council, replacing it with a weaker parliamentary council. These oscillations reflect a continued struggle between strong-man rule and demands for accountability.

From Discrimination to Civil War

The linguistic nationalism of the 1950s and constitutional centralisation of the 1970s pushed sections of the Tamil population toward separatism. Tensions boiled over on 23 July 1983, when Tamil Tigers ambushed and killed thirteen soldiers; anti-Tamil pogroms erupted in Colombo, killing an estimated 2,500–3,000 Tamils and destroying thousands of homes. This “Black July” marked the beginning of a brutal civil war. Over the next quarter-century, the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan state fought intermittently. Civilians bore the brunt of the violence: bombs ripped through bus stations, villages were razed, and child soldiers were recruited. After a final offensive that saw heavy civilian casualties, the government declared victory on 16 May 2009; by then roughly 100,000 people had died. The conflict left scars that still run deep—families searching for missing loved ones, war widows struggling to rebuild, and communities in the north and east coping with militarisation and underdevelopment.

Economic Crisis and the Aragalaya (2022)

The post-war years brought relative peace but also new challenges. Massive foreign loans for infrastructure projects, tax cuts that eroded revenue and policy errors—such as a disastrous 2021 ban on chemical fertilisers—left Sri Lanka heavily indebted and vulnerable to external shocks. By February 2022 the country had only US $2.31 billion in reserves to repay roughly US $4 billion in debt, and sovereign bonds accounted for nearly half of its external debt. The global recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and the collapse of tourism exacerbated the crisis. Foreign debt ballooned to 101 % of GDP by 2021, and inflation and power cuts became daily realities. Amid shortages of fuel, gas and medicine, children studied by candlelight and lines for petrol stretched for kilometres.

Frustration erupted into a mass movement known as “Aragalaya”—Sinhala for “The Struggle”. According to Freedom House, Sri Lankans mobilised in March 2022, and the protests coalesced into a countrywide movement demanding reforms to the political culture. Protesters were largely apolitical citizens rather than party activists; they chanted “Go Home Gota” (referring to President Gotabaya Rajapaksa) and occupied Colombo’s Galle Face Green for weeks. The government responded by declaring states of emergency, restricting social media and arresting activists. Yet the movement persisted: tens of thousands marched through the capital, and the presidential palace was briefly occupied. A United States Institute of Peace analysis notes that Sri Lanka faced its worst economic crisis since independence and that tens of thousands of ordinary people protested power blackouts, fuel shortages and soaring food prices while demanding the resignation of the Rajapaksa government. On 13 July 2022, after months of demonstrations and the May resignation of his brother Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled the country. He resigned from abroad, and Parliament elected Ranil Wickremesinghe president a week later. The protests, largely led by young people, showed a new civic consciousness and a willingness to hold leaders accountable.

A Resilient People and an Unfinished Story

Sri Lanka’s post-independence journey is a tapestry of aspirations and contradictions. The island went from dominion to republic, from Westminster parliament to executive presidency, from ethnic harmony to civil war and back to fragile peace. At various points, ordinary citizens shaped history: plantation workers who joined independence rallies, Tamil families who sought justice amid discrimination, mothers who protested the disappearance of their children during the war, and youth who camped at Galle Face Green in 2022 to demand accountability. Each chapter reveals a society grappling with identity, governance and fairness.

Today, as Sri Lanka navigates recovery from economic collapse and continues to debate constitutional reform, there is space for a new kind of politics—one that honours the island’s pluralism and empowers its citizens. Eunoia, the Greek word for “beautiful thinking”, invites us to imagine such a future. Sri Lanka’s history after independence teaches that progress is neither linear nor inevitable but forged through struggle, resilience and the courage of ordinary people to dream beyond the horizon.