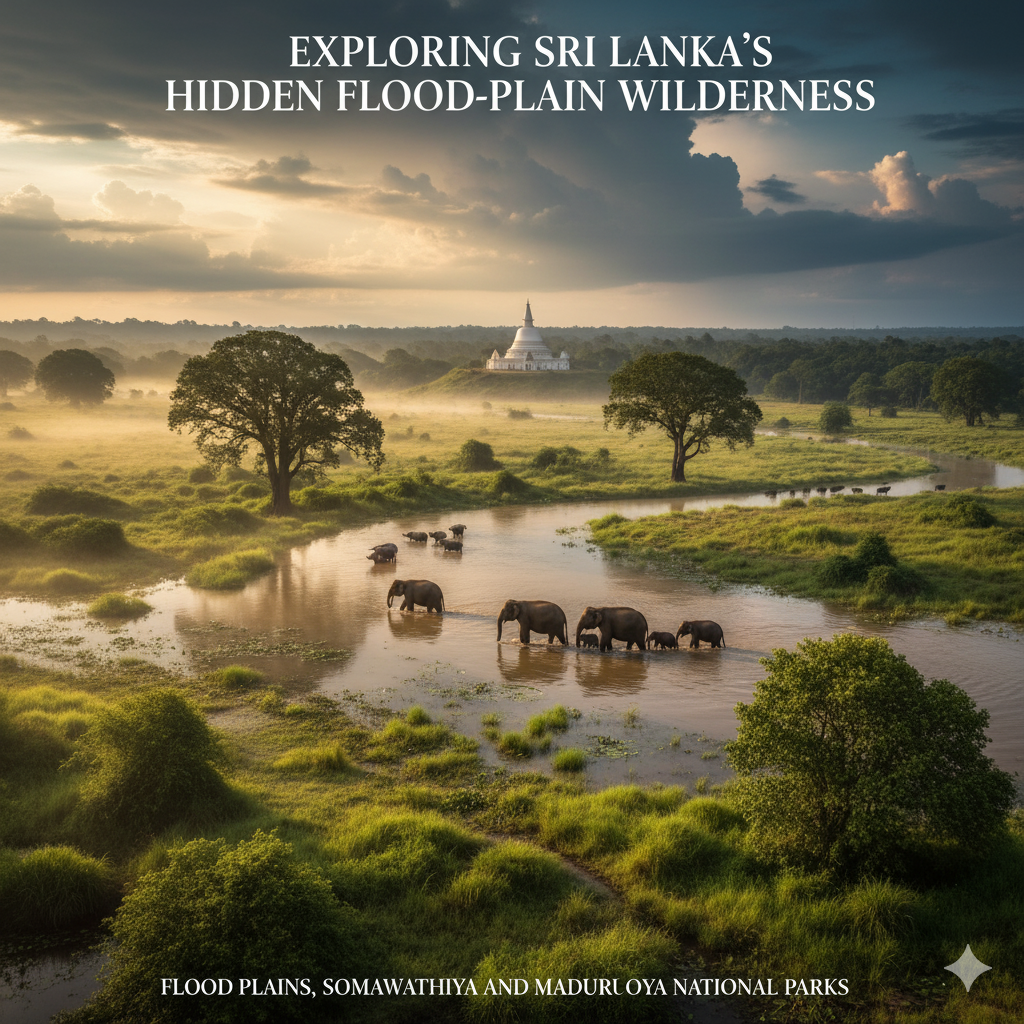

Exploring Sri Lanka’s Hidden Flood-Plain Wilderness: Flood Plains, Somawathiya and Maduru Oya National Parks

- November 14, 2025

- eunoialankatours

- 10:04 pm

Most visitors to Sri Lanka know Yala and Udawalawe, but few have heard of the flood-plain national parks along the Mahaweli River. Sitting east of Polonnaruwa, the Flood Plains, Somawathiya and Maduru Oya national parks form a connected chain of protected wetlands and dry forests. They were created in the 1980s as part of the Mahaweli development project, yet today they remain largely unexplored by mainstream tourism. During a recent expedition our Eunoia Lanka team discovered rich wildlife, ancient history and some very special elephants.

Flood Plains National Park

A landscape sculpted by water

Flood Plains National Park lies on the Mahaweli flood plain at elevations of 20–60 m above sea-level. The river runs north through the park and spills into shallow depressions known locally as “villus.” Around 38 of these lake-like basins dot the floodplains. During the north-east monsoon (October to January) the villus fills with more than a meter of water and continue to receive overflow from the Mahaweli headwaters during the south-west monsoon. When the floods recede the river deposits sand at the mouths of the villus, trapping water and creating a mosaic of wetlands, grasslands and swamp forests. This nutrient-rich habitat supports high primary productivity and, as we discovered, an astonishing diversity of life.

An elephant corridor and a home for water birds

The Flood Plains are an important part of the Mahaweli protected area system. They are the main elephant corridor that connects the national parks of Wasgamuwa and Somawathiya. Researchers thought that between 50 and 100 elephants crossed this passage in 2007. The park’s mix of grasslands and villus also provides a home for at least 75 types of migratory aquatic birds, including as marsh sandpipers, garganey ducks, ospreys, and painted storks.

Our local guides told us that people used to call a “vil aliya” or marsh elephant a “vil aliya.” This was a unique type of Sri Lankan elephant that lived in these wetlands. P.E.P. Deraniyagala, a biologist, wrote about Elephas maximus vilaliya in historical records. He said it was a different subspecies that lived only in the flood plains around what is now the Somawathiya region. People felt these elephants were bigger than other Sri Lankan elephants because they ate grasses that were high in nutrients in the marshes. Their feet were wider, which let them walk through deep mud. Scientists haven’t been able to identify this subspecies through genetic research yet, but we did see some extremely enormous footprints and a few strong males without tusks that locals say are the last “swamp elephants.”

The plants in the park show how the water levels change all the time. There are more than 230 different types of plants in the bigger villus and the marsh woods next to it. Creeping grasses like Cynodon dactylon (Bermuda grass) grow on the borders of the villus. Floating plants like Aponogeton (Ruffled Sword Plant, Crinkled Aponogeton, and Wavy-edged Sword Plant) and lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) grow in deeper areas. There are trees like Indian almond (Terminalia arjuna) and Madhuca longifolia (Indian butter tree or mowrah butter tree) in the swamp woods between the villus.

The park is home to fishing and jungle cats, jackals, wild boar, sambar, and spotted deer, in addition to elephants. We were lucky to observe a grey slender loris, a small monkey that only comes out at night. The water is also home to mugger and estuarine crocodiles, a lot of turtles, and a lot of fish.

Somawathiya National Park

Somawathiya is located downstream at the point where the Mahaweli River splits into two waterways. The park’s deltaic floodplain has roughly 20 villus and a lot of meadows. In 1966, it was made a wildlife sanctuary, and in 1986, it became a national park. The Somawathiya Chaitya, a stupa that is supposed to hold a relic of the Buddha’s tooth, is one of the most important parts. Some pilgrims say that amazing lights come from the stupa, which makes this wilderness even more appealing spiritually.

Somawathiya, like Flood Plains, has a lot of wetland plants. Creeping grasses grow around the villus, while the insides are home to hydrophytic species including Alternanthera sessilis (sessile joyweed and dwarf copperleaf) and Jussiaea repens (creeping water primrose). There are trees around the sides of the villu, such as Barringtonia asiatica (fish poison tree) and Mitragyna parvifolia (Kaim and Kadam). A survey from 2007 said there were between 50 and 100 elephants in the park. Many birds, such as painted storks, woolly necked storks, raptors, and groups of migrating waders, like Somawathiya’s marshes.

Maduru Oya National Park

Maduru Oya National Park, which was formed in 1983 to safeguard wildlife and the watersheds of five reservoirs, is two hours southeast of Polonnaruwa. Its scenery is made up of red earth plains broken up by an eight-kilometer range of stony hills and pockets of miocene limestone. The park is in Sri Lanka’s dry zone, where it gets about 1,650 mm of rain each year, mostly from the northeast monsoon.

Maduru Oya has cultural value. A stone sluice that is nearly 9 m high and 67 m long rests on top of an old earthen dam. Archaeologists think that part of it was erected before the 6th century BC. The Vedda people, Sri Lanka’s native hunters and gatherers, live in the park. It also has the remains of shrines and hermitages. The uplands are mostly dry mixed evergreen forest, and the reservoirs are surrounded by open grasslands that are kept up by fires that happen every so often. Vatica obscura is a rare plant that only grows in Sri Lanka’s dry zone. It is also known as Dummala or Sengi Mendora in Sinhala. There were between 150 to 200 elephants before the park was built, and a survey in 2007 showed about the same number. Along with a variety of raptors and aquatic birds, the area is home to sloth bears, leopards, langurs, and otters.

Visiting tips and responsible travel

These parks are far away and not very popular, which makes them even more charming. Polonnaruwa is the closest base, and it is roughly 230 km from Colombo. The Manampitiya bridge at Kaduruwela connects Polonnaruwa to Flood Plains and Somawathiya. It takes around 10 km and 15 minutes to drive there. Colombo is around 288 kilometres to the south east of Maduru Oya. Some portions of Flood Plains are closed to the public to protect wildlife, so you need a permit and a good guide. Our team set up visits with the help of local authorities.

The flood plain parks are at their most beautiful between January and April, when the water levels start to go down but the villus stay full. This is also the perfect time to see elephants walking through the wetlands and enormous groups of birds that are moving. Water is hard to come by during the dry months (May to September), therefore animals gather around the few remaining pools. To show respect for local people and animals, stay away from them, don’t make loud noises, and don’t feed them. Buy handicrafts directly from the Vedda community and learn about their culture to help them.

Why we love the Mahaweli flood plains

The experience of being in the wild is what makes these parks special. As ibises and storks flew away, our little boat sailed gently across a sparkling villu. We strolled along elephant tracks, knowing that some of the biggest elephants on the island used to live here and left deep footprints in the mud. The whitish dome of Somawathiya Chaitya rose over the trees in the distance, linking this untamed place to Sri Lanka’s old civilisation.

The flood plain national parks are a great place for nature lovers to get off the main path. They have a rich cultural history, a distinct wetland ecosystem, and the chance to see the rare marsh elephant. Eunoia Lanka Tours can help you see this little-known part of the island in a responsible way that helps protect the environment and the people who live there.