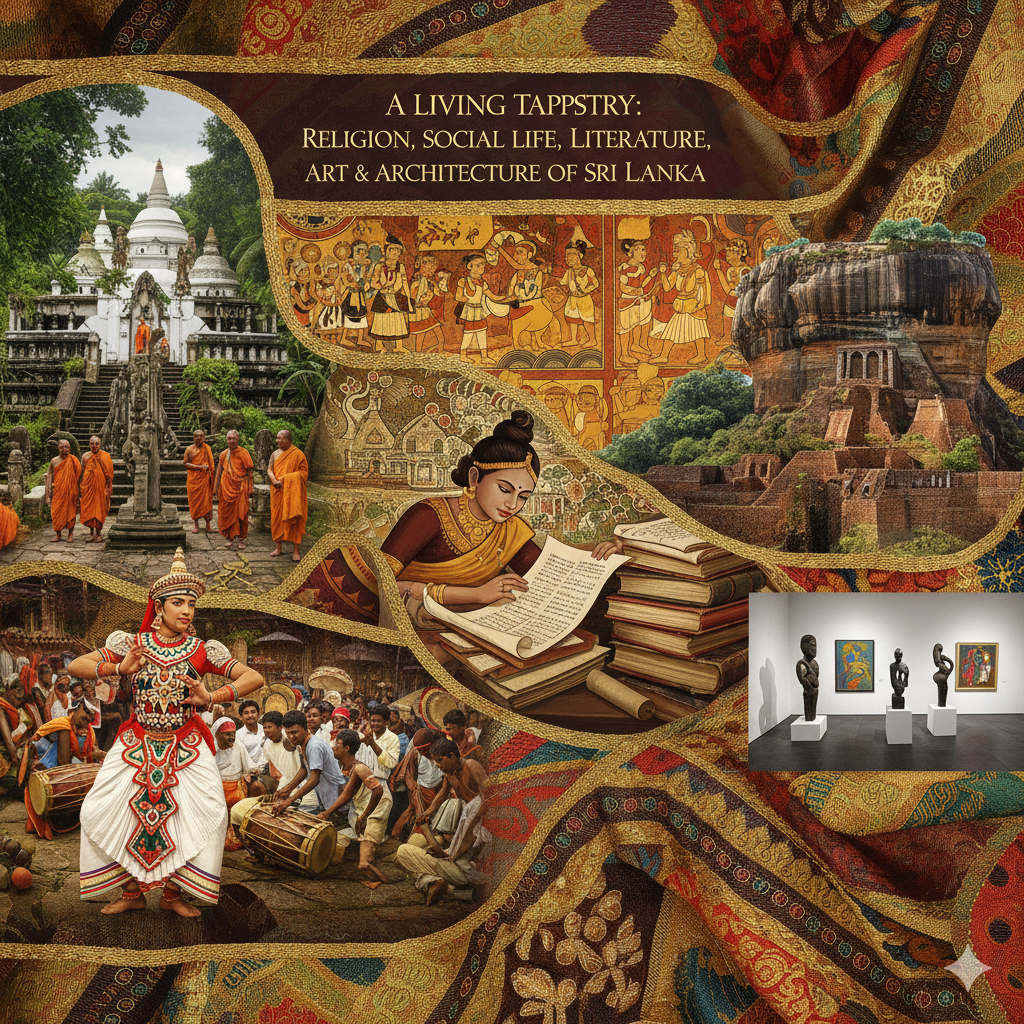

A Living Tapestry: Religion, Social Life, Literature, Art &Architecture of Sri Lanka

- November 14, 2025

- eunoialankatours

- 2:56 pm

Sri Lanka’s cultural fabric has been woven over millennia by travellers, traders and conquerors, but the golden threads are undeniably Buddhist. In the third century BCE Buddhism was introduced to the island and soon became intertwined with royal authority and everyday life. Over time the islanders absorbed Hindu, Muslim and Christian practices from later immigrants and colonisers, but the monasteries remained influential custodians of education, morality and the arts. Today Sri Lanka’s heritage still carries this fusion of belief, art and social norms.

Religion and kingship

Before the Mauryan missionary Mahinda reached the island, the Sinhalese who had migrated from north-India worshipped gods of nature and practised Brahmanism. Mahinda’s arrival during King Devanampiya Tissa’s reign (c. 250 BCE) marked a turning point. The king not only embraced the new faith but integrated it into governance: the royal residence was placed inside the “sima”—the monastic boundary—so that kingship would be guided by Buddhist principles. From that period until the 19th century, only Buddhists could legitimately rule the kingdom, and even today the Sri Lankan constitution requires the president to be a Buddhist. Monarchs sought the approval of the monastic community (saṅgha) during coronation ceremonies; in return the clergy legitimised their rule and offered spiritual authority. The resulting alliance conferred land and wealth upon monasteries and ensured that monks wielded real political influence.

While Buddhism became the state religion, Sri Lanka never became a religious monolith. Tamil immigrants from south India introduced Hinduism, Arab traders brought Islam and Portuguese colonisers spread Christianity. This mosaic of faiths is reflected in national symbols: the national flag uses colour blocks to represent the island’s three major ethnic groups and the four Bo-tree leaves in its corners symbolise the Buddhist virtues of loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity. The Tooth Relic, believed to be a remnant of the Buddha, remains a palladium of kingship and a focus of devotion for all communities.

Social life: flexible hierarchies and everyday pleasures

The ethos of Buddhism emphasised moral conduct and compassion over inherited status. Early Buddhist teachings such as the Vāsettha-sutta used analogies of trees and animals to argue that humans are not born into fixed castes and that spiritual achievement is superior to social class. Karma provided a framework for understanding social differences—people could attribute health, beauty or poverty to past actions—and this softened the caste system’s rigidity. As a result, Sri Lanka’s caste hierarchy evolved into a more flexible and forgiving structure than that of neighbouring India. Women enjoyed relatively high status; inscriptions from the third century BCE show that more than 250 women donated cave monasteries, and female scribes even left verses on the Sigiriya Mirror Wall.

Agriculture was the mainstay of the economy. Irrigation tanks (wāwa) and paddy fields fed the population, while coconut groves, rice, curd, honey and game meats enriched the diet. The island’s location on the maritime silk route made it a hub of international trade; natural harbours such as Manthai and Godavaya connected inland cities to merchants from China, Rome and Arabia. Sri Lanka exported gems, pearls, spices and elephants and imported silk, ceramics and glass. Brahmi rock inscriptions record gifts of caves by sailors, reminding us that navigators were part of society and that the sea trade funded religious institutions.

Education lay in the hands of the monasteries. Monastic schools offered free instruction in Buddhism, grammar, history, logic, arithmetic and medicine. Books were scarce and handwritten on palm leaves, so learning relied heavily on memorisation and recitation. Mass lectures were held three times a day, and villagers built maṇḍapa pavilions near monasteries to listen in. This system cultivated a “well-heard” (bahussuta) populace rather than merely a “well-read” one and helped to sustain the island’s high literacy levels.

Literature: from inscriptions to chronicles and verse

Sri Lanka’s literary tradition began with stone. The oldest evidence of writing on the island is a series of Brahmi inscriptions carved on the drip-ledges of cave monasteries from the third century BCE to the first century CE. These short texts state that specific caves were donated to the saṅgha by kings, chieftains or merchants and reveal a simple but widespread literacy. As the centuries passed, inscriptions grew longer and recorded land grants, irrigation works and tax exemptions for monasteries. The script evolved too, adopting Grantha characters under South Indian influence.

The island’s earliest narrative texts were monastic chronicles written in Pāli. The Dīpavaṃsa (“Chronicle of the Island”), compiled around the third or fourth century CE, recounted the Buddha’s visits to Sri Lanka, the arrival of the Bodhi tree and the Tooth Relic, and the spread of the saṅgha. In the fifth century the monk Mahānāma produced the more detailed Mahāvaṃsa, based on earlier commentaries and genealogies maintained since the third century BCE. Its 37 chapters intertwine the island’s history with Buddhist narratives, describing visits by the Buddha, Ashoka’s mission, the recording of the Pāli Canon and the deeds of kings from the legendary prince Vijaya to the third-century ruler Mahāsena. When combined with its continuation (Cūlavaṃsa), it forms one of the world’s longest unbroken historical records, spanning over two millennia. These chronicles, corroborated by inscriptions and archaeology, remain invaluable for dating events in Sri Lankan and Indian history.

Literary creativity was not confined to monasteries. The plastered Mirror Wall at Sigiriya fortress became a canvas for travellers’ emotions. Between the eighth and tenth centuries visitors—ranging from poets and governors to housewives—scribbled more than 1 500 verses addressed to the frescoed ladies on the rock face. Men praised the women’s beauty while female poets expressed admiration or envy. These poems, some of which are signed with female names, offer rare glimpses of the sensibilities and humour of ancient laypeople. Their presence shows that the literacy fostered by monastic education extended beyond the cloister.

Art and architecture: carving faith into stone

Sri Lanka’s earliest architecture is found in the drip-ledge caves of Mihintale and Dambulla, where monks lived in simple rock shelters in the third century BCE. The caves’ ledges diverted rainwater, and donors recorded their gifts with Brahmi inscriptions. Over the next several centuries, royal patronage shifted monks from caves into vihāra monasteries. These complexes offered better facilities and, by the fifth century CE, reached architectural maturity with elaborate moonstones, guardstones and carved frontispieces (vāhalkada) flanking soaring stupas. Gigantic monasteries such as the nine-storey Brazen Palace (Lōvamahāprāsāda) housed hundreds of monks, and megalithic columns still testify to their scale.

Sri Lankan architecture was heavily influenced by North Indian styles but developed its own forms under the guidance of monastic treatises. The Manjuśrī Vasthu Vidyā Śāstra, a fifth-century Sinhala manuscript, describes over 25 styles of Buddhist monasteries. Notable monuments include the colossal stupas of Jetavanārāmaya and Ruwanvelisaya and the rock-top palace of Sigiriya, whose planners integrated hydraulic gardens and mirror-polished walls into the natural landscape. Sigiriya’s design is considered a masterpiece; its builders even engineered the site to be environmentally sustainable. Sinhalese artisans also left an indelible mark in stone and paint. The cave temples of Dambulla and Hiriwadunna preserve vivid murals of the Buddha and cosmological scenes, while the Isurumuniya temple at Anurādhapura houses a celebrated secular sculpture of two lovers.

Sri Lankan art was overwhelmingly religious. Stone sculptures, cave paintings, temple murals, processions and mask dances centred on the Buddha or Buddhist cosmology. Secular art existed but was rare; the Ranmasu Uyana pleasure garden in Anurādhapura and the Isurumuniya lovers’ panel are among the few examples. Foreign influences continually enriched local styles—Roman coins, Indian gold statuettes and Chinese ceramics unearthed near ancient ports remind us that artisans and patrons drew inspiration from their international trade links.

A living heritage

By the late 19th century a Buddhist revival responded to Christian missionaries and British colonialism. Reformers such as Anagarika Dharmapala promoted education and printed books, and Sri Lankan monks helped re-establish Bhikkhunī (nuns’) ordination abroad. Meanwhile Hindu deities, astrology and local spirits were woven into popular Buddhist practice, creating a syncretic faith. The modern constitution still protects Buddhism, but Sri Lanka remains multi-religious and multi-ethnic, with vibrant Hindu, Muslim and Christian communities.

Sri Lanka’s history shows how religion, social life, literature, art and architecture are interdependent. Buddhism offered a moral compass and political legitimacy; social norms emphasised compassion over birth; monks preserved history in chronicles and taught generations of boys and girls; artisans carved faith into rock and paint. The result is a civilisation that has continually absorbed new influences while honouring its ancient roots. For travellers today, the island’s monasteries, stupas and frescoes are not relics of a dead past but living testimonies to a culture that still cherishes learning, artistry and spiritual reflection.