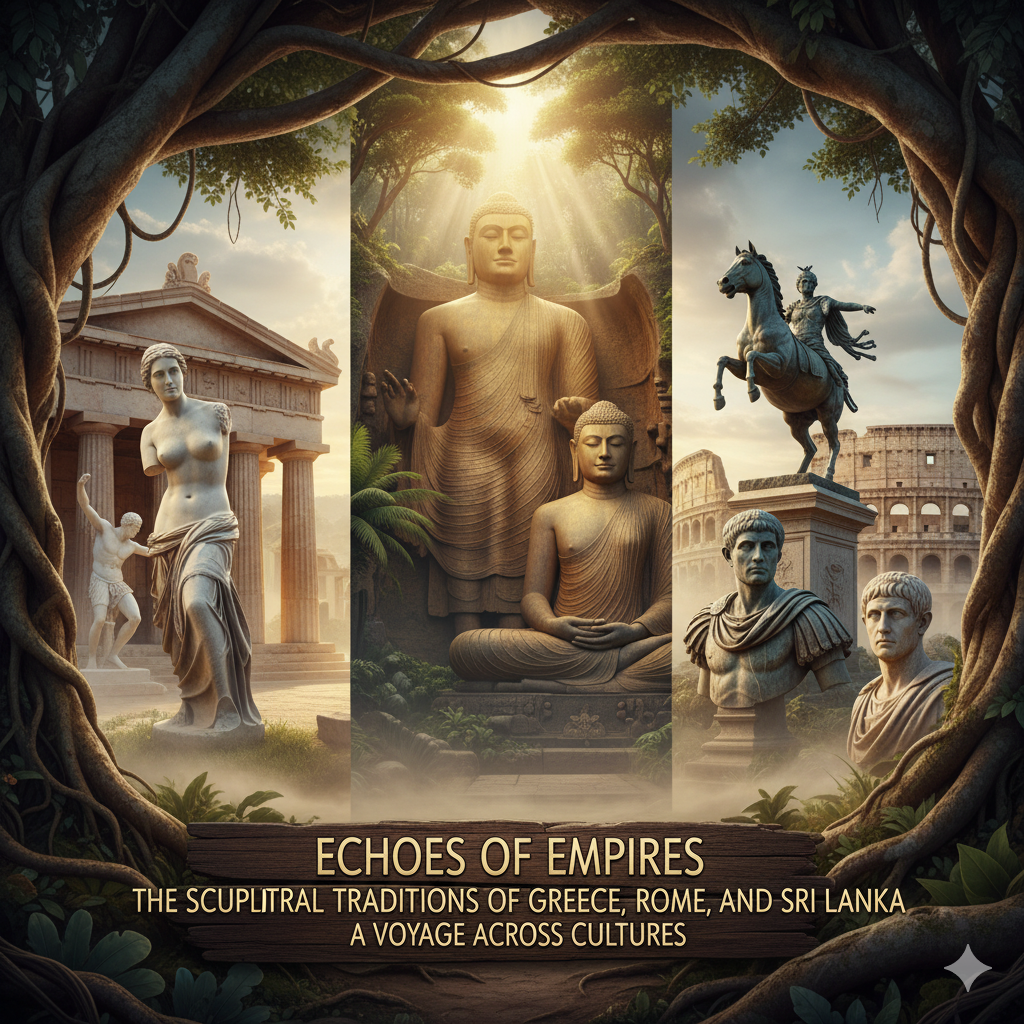

Echoes of Empires: The Sculptural Traditions of Greece, Rome, and Sri LankaA voyage across cultures

- November 13, 2025

- eunoialankatours

- 7:24 pm

One of the oldest ways for people to talk about beauty, power, and spirituality is via sculpture.

Greek sculptures throughout the Classical period tried to create an idealized version of the human body. Their marble and bronze gods, heroes, and athletes were all in perfect harmony and balance, with meticulously calibrated proportions and muscular structure. Greek sculptors wanted to show gods and athletes as perfect beings that represented the best of what people could be, as a blog on classical sculpture points out. The things they wrote about were mythology and civic pride. Statues of gods, winning athletes, and legendary scenarios filled temples and public venues. People assumed that emotions were held back, therefore expressions were frequently calm and controlled.

Roman artists, on the other hand, learnt and changed Greek techniques while creating a radically new style of sculpture. Roman patrons liked Greek originals and brought Greek craftsmen to Italy, but over time they fashioned their own style. Roman sculpture during the Imperial period (1st–4th centuries CE) was realistic and unique. Portraits of emperors and politicians included wrinkles, baldness, and other flaws to show character and authority. Their work had practical uses, like official portrait busts, triumphal monuments, sarcophagi, and commemorative reliefs that honored real people and events. Roman sculptors also changed up their methods, utilizing colored marbles and ivory and even reworking older pieces. This shows that they were practical and creative.

Greco-Buddhist art is where Greek and Roman ideas meet the Buddha.

Alexander the Great’s Hellenistic conquests opened up new cultural paths between the Mediterranean world and South Asia. In the area known as Gandhara (now parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan), local people adopted Buddhism and Greco-Roman art styles. According to Smart history, Gandharan sculpture is an art type that appeared between 100 BCE and 700 CE. It mixed Hellenistic, Persian, and Kushan styles to create some of the first anthropomorphic images of the Buddha and bodhisattvas.

- The first bodhisattva reliefs (from the 1st century BCE) have a stiff Graeco-Roman style, with bodies that are angular and drapery that is deeply carved.

- In the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, as Gandharan art got better, bodhisattvas were carved more realistically, with thick, flowing robes that looked like Roman togas. Their individual moustaches and different hair knots (a Gandharan version of the Buddha’s ushnisha) made them look more human.

The mix of Hellenistic naturalism and Buddhist art had a big effect on a lot of things. Britannica says that Gandhara’s artists borrowed ideas from Roman art, like vine scrolls, cherubs, and acanthus, and showed the Buddha with a young, Apollo-like appear and Roman-style clothes. These standardized pictures of the Buddha spread along trade channels and became templates for sculptors in Sri Lanka and South Asia.

Amarāvatī: an Indian respond to classical beauty

Gandhara looked to the west, but the Amarāvatī School in southeastern India created its own lively Buddhist style during the Satavahana era (2nd century BCE–3rd century CE). The Amarāvatī workshops etched stories and events from the Buddha’s life into white limestone stupa railings. In the beginning, panels were symbolic: lotus blossoms stood for his birth and empty thrones stood for his enlightenment. But by the 2nd century CE, sculptors were making life-sized, humanized Buddhas with full bodies and complicated positions. Figures became thin and moving, with swirling clothes and sinuous movements etched in high relief. Compositions filled whole slabs like a stone picture. Ayaka pillars, purna-kumbha (overflowing pot) patterns, and complicated lotus scrolls are some of the things that make the school stand out.

The Amarāvatī style spread fast along the sea. The Wisdom Library says that the lower Krishna valley spread Andhra culture throughout South and Southeast Asia. Sri Lanka, which is immediately over the Indian Ocean, was “heavily touched by Indian influences” when Buddhism came to the island. Scholars agree that Amarāvatī had an effect on Sri Lankan art. For example, decorative moonstones at temple entrances and guard stones with nāga images in Sri Lanka are similar to Amarāvatī examples. Some early Sri Lankan Buddha statues, such the ones around the Ruwanweli Dagaba, even have Amarāvatī-style draperies and attitudes.

The development of a unique Sri Lankan style

Sri Lanka took in these ideas, but over time it developed its own style of sculpture. Images from the early Anuradhapura period, like the Toluvila Buddha (4th–5th century CE), have a serene, meditative quality. The Toluvila statue is made from a single block of granite and represents the Buddha sitting in the dhyana mudra with his legs crossed. Unlike many Indian sculptures, it doesn’t have long, hanging earlobes; instead, it has three subtle lines on the neck, which are thought to be the result of Mathura-school influence. The shoulders are just over a meter apart, which shows that the island likes balanced but strong proportions.

In the 12th century, Sri Lankan sculptors made some of their best work at Gal Vihara in Polonnaruwa. A single piece of granite rock was cut into four huge statues: two sitting figures, one standing figure, and one reclining Buddha. People think they are the best examples of ancient Sinhalese rock carving. The biggest seated statue is 15 feet 2.5 inches tall and rests on a lotus-shaped throne with makara (mythical crocodile) designs and four small Buddhas on it, which suggests Mahayana influence.

A tiny seated statue of the Buddha is in an artificial cave. Behind the Buddha are two four-armed gods, Brahma and Vishnu, with a carved halo around them.

The figure, which is 22 feet 9 inches tall, leans back a little and has its arms crossed over its chest. Some historians think that the sad look on Ananda’s face and the fact that it is close to the reclining image show that he is mourning the Buddha’s death. Others, like the archaeologist Senarath Paranavithana, think that the Buddha is showing compassion for the suffering of others (the para-dukkha-dukkhitha mudra). The reclining Buddha is one of the largest in Southeast Asia, measuring 46 feet 4 inches long. It shows the Buddha’s parinirvana, or last passing. The statue is lying on its right side, with its right arm supporting its head and its left arm reclining along its body. There is a lotus engraved on the soles of the feet, and the left foot is slightly pulled back to show that the Buddha has died instead of just sleeping.

The style of Gal Vihara is different from that of older Anuradhapura images. The Buddhas have wider foreheads, and their robes are carved with two parallel lines instead of the single line that was common in earlier statues. These changes are directly linked to Amarāvatī influence. To make the rock face smooth enough to carve, they dug out over 15 feet of rock at the site. This is what makes it distinctive in Sri Lankan architecture. Paranavithana, an archaeologist, says that these statues were once covered with gold.

The blog Original Buddhas did a later study that showed how the broad forehead and double robe-lines at Gal Vihara show influence from the Amarāvatī school. The article also says that early Sinhalese craftsmen cut the rock face 4.6 m deep and made four statues in different sizes and poses, which shows their amazing engineering skills. The same article goes on to say that the smaller seated statue features a carved lotus seat, a throne with lots of decorations, and a halo with gods on either side. The standing figure’s distinctive cross-armed mudra shows compassion. It says that Paranavithana thinks the standing figure shows the Buddha looking at the Bodhi tree during his second week after becoming enlightened.

Looking at the different customs

| Custom | Important parts | Some good examples |

| Sculpture from Greece | Mythological subjects; idealised, harmonious human forms; focus on proportion, balanced stances, and controlled expressions. | Polykleitos’ Doryphoros with the Parthenon marbles. |

| Sculpture from Rome | Realistic portraits that show personality and traces of ageing; used for memorials or politics; made from a variety of materials that can be reused. | Portraits of emperors, like Augustus of Prima Porta, and triumphal reliefs. |

| Gandhara: Greco-Buddhist | A mix of Hellenistic, Persian, and Kushan styles; the first anthropomorphic Buddhas; early reliefs were stiff and Graeco-Roman; later figures were more realistic, wearing thick robes, moustaches, and different top-knots.patterns like acanthus and vine scrolls | Bimaran reliquary with standing bodhisattva (Metropolitan Museum). |

| The Amarāvatī School | White limestone panels with narrative reliefs; ayaka pillars and lotus patterns; early symbolic panels change into life-sized Buddhas with thin, moving figures and flowing clothes. | |

| Sri Lankan style | The early Anuradhapura images, like the Toluvila statue, show a peaceful, contemplative state, strong proportions, and slight Mathura influences. Later Polonnaruwa sculptures at Gal Vihara feature wider foreheads and double robe lines that were influenced by Amarāvatī. Large rock-cut Buddhas show off both engineering skill and a calm demeanor. | Toluvila statue at the National Museum of Colombo; seated and reclining Buddhas at Gal Vihara. |

Why these differences are important

For people who are visiting Sri Lanka, knowing about these sculptural traditions makes every trip to an old stupa or rock temple more interesting. Greek and Roman artists set standards for form and realism that still affect how people around the world see art. Their effects spread to Gandhara, where Buddhist pictures took on human shape and Greco-Roman drapery, and Amarāvatī, whose dynamic reliefs influenced artists all around the Indian Ocean. Sri Lankan sculptors took in these styles but made something new: statues with wide foreheads, flowing robes, and a calmness that shows how devoted the island is to Buddhism. When you stand in front of the rock-cut Buddhas of Gal Vihara, you can hear echoes of Apollo, the skill of the Amarāvatī carvers, and the Buddha’s deep compassion. This shows how Sri Lanka has been a part of this artistic conversation for ages.